Camera Obscura History and the Discovery of Photography

Michael • updated November 27, 2022 • 10 min read

Michael • updated November 27, 2022 • 10 min read

The term “camera obscura” is Latin for “dark chamber,” and it refers to a simple piece of equipment used to create images that led to the discovery of photography.

The English word for today’s photographic gadgets is simply a contraction of this name, which is “camera.”

The camera obscura is, at its most basic, a simple box (or room) with a small hole in one side. Light will travel through the hole and reflect an upside-down image at the opposite wall.

The image sharpens as the pinhole becomes smaller, while the light sensitivity drops. The image is always upside-down while using this simple equipment.

It is also feasible to project a “right-side-up” image by using mirrors, as in the 18th-century overhead version.

Content

» Listen

The camera obscura is the oldest method of image reproduction. A dark room or, in a lesser variant, a dark and lightproof box with a hole determines it. Light rays fall on the object to be photographed and are focused in the same way that they are now using a lens.

Because light rays cannot pass through the hole, they are inverted in the image’s box or room. The image is appropriately projected and reversedly presented on the back wall. The finer the image, the smaller the hole in the camera obscura.

A simple experiment can help you understand the effect of a camera obscura. In a dark room, use the keyhole opening as an exposed source. Place a white piece of paper in front of it. The light from the keyhole falls onto the sheet of paper.

You can see the image of the room on the paper where it is presented overhead if you move back a few steps with the sheet and away from the keyhole as the light source. The box functions as a dark room in the pinhole camera, and the hole serves as the light passage opening, which is then very small in order to display a sharp image.

The operation of a camera obscura was already known by the end of the 10th century, having been described in detail by Arab science, particularly by Abu Ali ibn al-Hasan – known by the name Alhazan (965-1038), who used the basic concept of the camera obscura to explain the formation of the image in the eye.

There are even older descriptions of observations of the phenomena and the light effects produced by a camera obscura: from the 5th century BC in certain Chinese philosophical works and from the 4th century BC in an Aristotelian reference (384-322 BC). However, until Alhazan, no connection was drawn to the origin of the optical image.

During the Middle Ages, Roger Bacon continued Alhazan’s studies on light reflection and refraction, and while he was aware of the camera obscura’s existence, he never described one.

Leonardo da Vinci was a driving force in the development of the camera obscura during the Renaissance, to further investigate the workings of vision, the behavior of light, and the principles of geometric perspective, always in connection with painting methods.

Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by the phenomenon of the camera obscura, which allowed “the rays of light to pass through a small opening without blurring together”.

Regarding da Vinci’s role in the development of the camera obscura, it should be mentioned that he was the first to install a lens in the mouth with the aim of obtaining sharper images.

The first written mention of lenses dates back to the mathematician Girolamo Cardano (1501-1576) in 1550, although it was the scientist Giovanni Della Porta who spread the news throughout the world eight years later.

Giambattista della Porta (1535 – 1615) promoted an improved camera obscura, and painters adopted his technique to recreate real-life situations on canvas.

Della Porta’s work was written in a simple and popular style, which is why it was crowned with great success and was translated into Arabic and various European languages. This explains why the author is often referred to as the inventor of the camera obscura.

In the 17th century, Robert Hooke (1653-1703) constructed various cameras obscura. He tried to reproduce the round shape of the retina with concave screens at the bottom of the camera.

He thus tried to represent the mechanism of human vision. He also built various models of portable Cameras Obscuras, which served as illustration models for guidebooks of the era and for exploring topography.

Another use of the camera in that century was for amusements at court, to entertain royal parties and satisfy the curiosity of courtiers. The many possibilities of the camera could be exploited in many witty inventions.

For example, in 1642, the mathematician Pierre Herigone reported a camera obscura in a glass that worked when the glass was filled with white wine.

Johann Zahn (1641 – 1707) was a mathematics professor at the University of Würzburg. His primary area of expertise was optics, which included astronomical observation.

He improved on Johann Sturm’s 1676 reflex camera with an upright image by adding a telescopic lens consisting of two pieces with varying focal lengths, one behind the other to create a larger image (reflex camera obscura).

To prevent reflections, he also colored the exposure chamber black. Except for the shutter system, the invention is a photographic camera prototype. He built a mobile camera obscura in 1686.

A mirror positioned within the camera at a 45-degree angle to the lens projected the image upward onto a bottom glass screen, where it could be easily traced.

A rectangular extension could be utilized to focus the image. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe also traveled with a device of the same kind.

At the time, his book “Oculus artificialis teledioptricus sive telescopium” (The Long-Distance Artificial Eye, or Telescope) was a classic work in the discipline of optics.

His book, published in 1685, covers topics including the Theory of Optics, Microscopes, Telescopes, Mirrors, and Lenses.

There are numerous studies that attempt to establish a link between Dutch painting and the use of the camera obscura because of its realistic representations.

More precisely, they tried to show how Vermeer used the camera obscura. For this purpose, they looked for motifs painted by him, which were difficult to perceive with the human eye, but could be illustrated with the camera obscura.

Painter Johannes Vermeer, created the masterwork “Girl with a Pearl Earring,” also known as the “Mona Lisa of the North.” which is suspected of using a camera obscura with a lens, which would explain the shimmering pearly highlights typically visible in Vermeer’s paintings.

Source: renegerritsen.com

He used to create sceneries that were so lifelike that they could be mistaken for photographs. Vermeer’s manipulation and utilization of light were so powerful that you couldn’t tell if it was done by a human or a machine.

“With the invention of ground glass lenses 400 years ago, the camera obscura became a practical tool for painters who wanted to draw the most accurate picture of nature.”

Despite the fact that it appears improbable that a machine could have assisted in the creation of such emotional, human paintings, thanks to fresh discoveries, many experts concur with this theory.

Rembrandt and Caravaggio are two more masters who have been “accused” of utilizing such techniques.

There is no clear evidence of the systematic use of the camera obscura by the great artists and painters in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The importance of landscape painting throughout the 19th century is evident in academic education, as teaching about the use of the camera obscura was given the rank of a major subject in the study of the high arts.

Some scientists also found in the camera obscura the answer to their need for technical tools to realize high-quality images in their scientific publications.

The 18th century – the period before the invention of photography – is the most important in the history of the camera obscura, both because of the constantly improving technology and the construction of new models and because of its wide dissemination through a large number of publications.

In the second half of this century, the “Encyclopedia” of Didderot and D’Alambert describes on two pages of the article “Dessin” two well-known and in practice used models of the camera obscura of that century.

In 1826, the Frenchman Joseph Nicéphore Niépce (1765 – 1833) took what is regarded as the world’s first photograph. Niépce bought a camera obscura with a meniscus lens in an optician’s store in Paris in 1826 and invented a method to permanently preserve images.

The world’s first snapshot shows the courtyard of Niépce’s estate at Le Gras as seen from Niépce’s study. The courtyard and outside buildings are seen. The sun’s location, as well as the changing light and shadows, suggests an exposure length of eight to 10 hours.

A tin plate holds the subject. The photochemical technique is based on bitumen’s unique features. The bitumen, which had been dissolved in lavender oil and applied to the plate in a single layer, solidified in the areas exposed to light, but the unexposed parts of the picture remained soft and soluble and could be washed out in a bath of lavender oil and turpentine.

The end consequence was a long-term direct positive. Niépce described his shot with the word “heliography,” which literally means “sun drawing.”

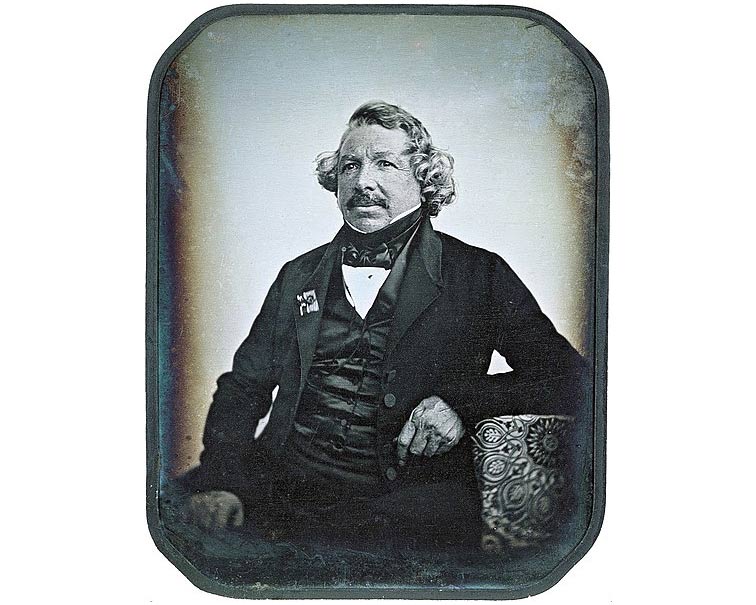

Niépce’s work was never recognized. For a long time, his subsequent partner, Louis Daguerre (1787–1851), was regarded as the founder of photography, according to a photograph he took in 1838.

We have a article that explains when did portrait photography start.

It wasn’t until the collecting coupler Helmut and Alison Gernsheim discovered of Niépce’s first heliograph predated the creation of photography. In 1898, “The View from the Window at Le Gras” was displayed at the Crystal Palace in Sydenham. It was then lost for more than a half-century until it was rediscovered by collectors Helmut and Alison Gernsheim.

Niépce’s iconic painting was presented for the last time in Europe in a Munich exhibition in 1961. The Gernsheims donated their complete collection of historic pictures to the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center in 1963. They also left the world’s first photograph to this institution as a gracious gift.

Louis Daguerre, born on November 18, 1787, in Cormeilles, near Paris, began his career as an architect’s apprentice before honing his sketching skills as a decorative painter in the theater. In Paris, he made his artistic breakthrough by establishing a so-called diorama, which drew viewers in with illusionistically painted city views, for which Daguerre also used camera obscura projections.

Simultaneously, he began experimenting with repairing the projected images. He made close friends with Nicéphore Nièpce, a generation his elder, who was undertaking similar attempts at the same time and who succeeded in 1826 in producing the world’s first light-fixed photograph, a view from his study window. After Nièpce’s death in 1833, Daguerre perfected his own method.

The politician Francois Arago presented photography as an invention to the Paris Academy of Sciences in 1839. Arago praised photography and its inventor, Louis Daguerre as France’s gift to the world exactly 50 years after the French Revolution. It was a form of conflict between nations, but one without weapons, because it was about the competition of ideas and, ultimately, about business.

“…the daguerreotype is not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a chemical and physical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself.” Louis Daguerre

Daguerre had perfected the first photographic process that could also be sold. His daguerreotypes, however, which included portraits as well as architectural views or still life, were manufactured as one-of-a-kind specimens. His plan did not contain duplication, but this had no effect on the early global success of his newly devised method.

Daguerre had figured out how to clearly define his photographic technique so that others might comprehend it as well. One of the most severe challenges that Nièpce, as well as Talbot, faced was the inability to record their processes in detail. In fact, only Daguerre had arranged his method in such a way that others might understand it.”

As a result, Daguerre first won the competition for the invention of photography and gained a lifetime income. The government’s support for his method was intended to cement France’s dominance in the field of nascent photography. In the 1840s, there were numerous daguerreotype workshops, particularly in Paris.

“With its formal clarity, sharpness of detail, and closeness to painting, the daguerreotype had a major influence on the aesthetics of photography.”

Interestingly, the daguerreotype was preferred in two very opposite sectors at the time: science photography and, strangely, nudist photography. Thus, the view of female nudity in that age is transmitted to us now through daguerreotypes. “

Daguerre died in the summer of 1851, and the technique he named would only survive for another two decades. Following that, photography shifted to less expensive negative/positive procedures that allowed for an unlimited number of prints. Daguerre’s innovation would go down in history as an interlude, although a pivotal one.

Build a camera obscura using items you have around at home in a few minutes.

Materials and tools you need:

Watch the Video for instructions

If you don’t like to build a pinhole camera, here are six cameras obscura that you may visit today to see the forerunner of modern photography.

More about the camera obsura:

The history of camera obscura

Catching Up With Camera Obscura

The precursor of the photographic camera

This is the Oldest Surviving Photo of the Moon

Alhazen introduced method in experimental psychology

Ibn al Haitham was the first to show the foundations of projection using a camera obscura. He was able to invalidate the theory that the human eye emits rays when it stares at something. He demonstrated that, on the other hand, every exposed item reflects the photons that the eye perceives.

As a result, the camera obscura is constantly associated with the portrayal of the human eye. This effect and the possibilities of the method were already of interest to Aristotle and Leonardo da Vinci. The camera obscura was employed in the Renaissance to trace images on canvas, for example.

The image reversal principle is the foundation of photography and the first photographic cameras. As a result, the camera obscura was crucial not only for photography but also for telescopes and astronomical investigation of the stars. While the initial devices were still somewhat huge,

Johannes Zahn invented the first compact camera with interchangeable lenses in the 17th century. The image was visible anytime light entered the camera. Permanent photographs were not yet possible.

Nonetheless, the camera obscura phenomenon was employed and further refined for succeeding photographic devices.

The premise of the pinhole camera, created circa 284 BC, is the projection of an object on the rear of a light-tight box with a hole. It is one of the oldest optical systems for image projection and produces an image by using straight-line light propagation.

The construction is fairly basic, requiring only an opaque shell with a small opening and a translucent screen opposite. This meets the criteria of the camera obscura and allows the effect to occur.

Straight-line light propagation allows for the creation of the image. When a lit candle is placed in front of the camera obscura, the light from the flame spreads evenly in all directions.

Light is only reflected when it strikes an object. This is the box with the pinhole camera opening.

Only a focused beam of candlelight enters the box and is projected onto the back wall, with the lower point of the candle at the top and the upper point at the bottom.

The reverse picture is then generated on the back wall or the light-sensitive screen, which has its sides flipped at the same moment. The image is exhibited more clearly when the light is weaker and the hole in the pinhole camera is smaller.

The image quality is also affected by the object’s distance and the size of the box. The image becomes smaller as the distance between the pinhole and the screen increases. A lens later eliminated these fluctuations in sharpness loss.

In fact, the camera obscura was not yet a camera in the modern sense, but rather a dark room or darkroom. Alchemists in the Middle Ages utilized a dark, scaled-down box with a mirror or lens to reveal unseen worlds. This did not work, but the camera obscura has since served as a metaphor for human understanding.

What are your thoughts on the camera obscura, let us know in the comments!

Related Articles

Photography History

Photography History

Your thoughts and questions